Ruth Hubbard, The University of Queensland

Across the developed world, looking older than your chronological age is considered a drawback. Western societies value physical beauty and vitality while science is actively trying to find a way to reverse the ageing process altogether.

This is probably why a study published in the latest issue of The Australasian Journal of Dermatology, that concluded Australian women report more severe signs of facial ageing sooner than other women, received a fair amount of media coverage.

It generated alarming headlines such as:

Why Aussie women are ageing up to 20 years faster than US women

Like the research paper itself, these articles focused on photoageing – the damage done to our skin by exposure to high UV levels. But there is quite a bit more to the ageing process than wrinkles and crow’s feet. And the “20 years faster” claim also deserves scrutiny.

How was the study done?

The paper was published in a reputable, peer-reviewed outlet – the official journal of the Australasian College of Dermatologists and the New Zealand Dermatological Society.

The sample was 1,472 women aged 18-75 (averaging late 40s) from Australia, the UK, Canada and the US. They were recruited between December 2013 and February 2014 from an internet-based polling panel.

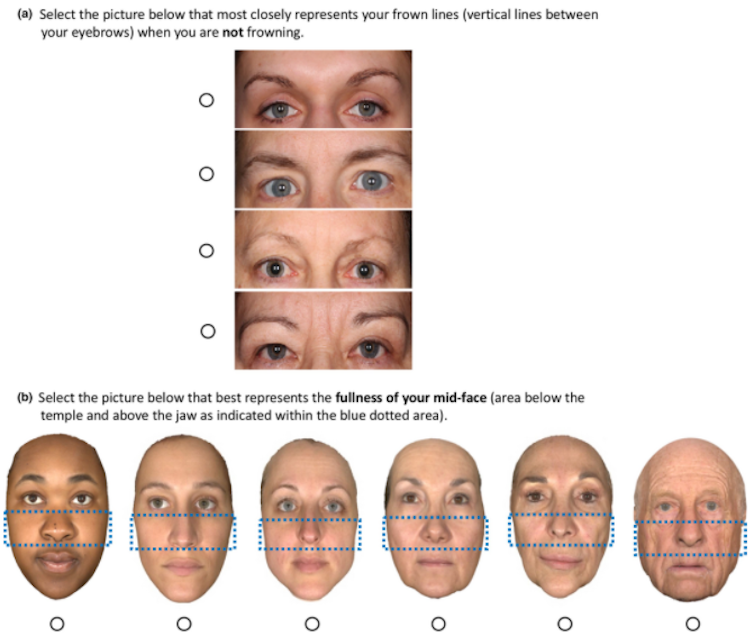

The women were asked to use a mirror to compare their own facial features to photographs illustrating increasing signs of ageing (from none to severe) for eight different characteristics.

These were static forehead lines, crow’s feet, glabellar (frown) lines, tear troughs (groove between lower eyelid and cheek), mid-face volume loss, nasolabial folds (the two skin folds that run from the nose to the corner of the mouth), oral commissures (the corners of the mouth) and perioral lines (wrinkles around the lips).

They were asked to choose one image – out of four to six (depending on the feature) – that most represented their current facial features in the absence of facial expression.

People were excluded if they had significant facial trauma or burns, or if they’d had any form of plastic surgery, including Botox, fillers or laser treatments.

Skin colour can be categorised by its typical response to UV light: from type one, which is very fair skin that always burns and never tans, to type six, which is dark brown skin that never burns and always tans. In this study, only women with skin types one to three were included.

What were the results?

Australian women reported more severe facial lines and higher rates of facial change with age than women from the other countries, particularly those from the US. Though, interestingly, for women in their 70s, the average severity of facial lines was generally similar from country to country.

The researchers then looked at the 30% or more of women who reported moderate or severe ageing for all features. They found that in Australia, this occurred:

from the ages of 30-59 years […] but this proportion of US women did not report this level of severity until the ages of 40–69 years.

This seems to be the crux of the paper, and the finding that underpins the conclusion that we’re ageing 20 years faster than we should be.

The study has many strengths. It is elegantly written and some aspects of the methodology are robust. For example, Asian women experience skin wrinkling later than Caucasian women, and smoking is associated with more skin ageing. So the researchers made sure these factors were not responsible for the results by adjusting their analyses for age, race and smoking status.

The results are certainly plausible and consistent with other studies. People living in Australia are exposed to higher levels of UV radiation, which is responsible for most age-associated cosmetic skin problems in fair-skinned people.

A study of 1,400 randomly selected residents of a Queensland community used casts of the back of the hand and dermatological assessment to show that premature ageing of the skin was associated with high sun exposure during leisure or work.

What is the problem?

There are two main limitations of the study. First, the differences in self-reported facial lines may be statistically significant across countries, but this does not mean they are clinically significant.

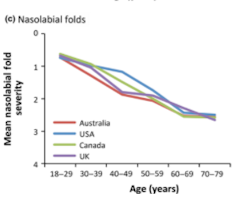

Figures in the research plot the average severity of each line against age, with different colours representing each of the four countries.

Participants had up to six photographs to choose from, so the severity scale could range from 0 to 6. In the figures, the colours follow very similar trajectories and often overlap. Even the biggest gap between the countries looks like it represents a difference of 0.3 or 0.5. This is relatively small and may not be something anyone could observe.

Second, it is not clear why the researchers decided to focus on the 30% or more of women who reported moderate or severe ageing for all features. No other studies have used this cut-off.

The authors said that:

this cut-off was chosen to yield the best sensitivity in detecting differences in facial ageing severity among countries.

This suggests fewer differences were found than if another cut-off was considered. For example, would there have been significant differences when 20% of women rated each feature as having moderate or severe signs of ageing? Or 50%? Or 90%? Choosing a cut-off which is not based on a clinically meaningful or validated proportion raises questions about the true significance of the reported changes.

What else should we consider?

The title of the study is an accurate reflection of its content, stating that it is a comparison of self-reported signs of facial ageing. But the accompanying media coverage implies Australian women are ageing prematurely.

There is no evidence this is true. Robust studies of many tens of thousands of women show Australians are very similar to women in Europe and North America, through middle age to the extremes of old age. The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health provides a wealth of data in this field.

More important markers of health status in older people – disability, self-rated health, depression and anxiety, dementia – are all comparable. Life expectancy at birth (84.4 years for women) is slightly higher in Australia than in the other countries studied in this paper.

What is the take-home message?

Despite the methodological limitations of the study, in some ways it is good for it to be widely publicised.

Just like public health campaigns about premature ageing were used to decrease smoking rates in women (and thus reduced multiple smoking-related disease), the message Aussies may be looking older because of UV radiation may encourage us to limit our sun exposure. This would then reduce melanoma and other skin cancers.

As a type one redhead living in Brisbane, I shall certainly continue to wear my hat. – Ruth Hubbard

Peer Review

This Research Check fairly outlines the strengths (number of participants, accounting for age and other factors like smoking) and limitations (self-reporting and limitations in adjusting for confounding variables).

It also addresses the issue that caused the alarmist headlines – the graph showing when more than 30% of women rated a facial feature as reflecting moderate or severe signs of ageing. The author correctly points out there is no justification in choosing the 30% cutoff, that no other study uses it and that it is unlikely to be of any clinical significance.

More importantly, the Research Check analyses the figure that presents data for women across the various age groups. It points out most of the curves overlap, and that differences between groups of women are actually hard to see.

I would go even further and say that while the 95% confidence interval - an important estimate of variation - is presented in the tables, it is not applied to the graphs. If you show the 95% confidence intervals reported in the tables to the graphs, you would see most of the values for the women in other countries would not be significantly different to those in Australia.

For example, in the graph showing nasolabial folds, women in the light-poor UK have the same (age 18-29, 40-49) or marginally worse (age 70-79) nasolabial folds than in Australia.

This Research Check gives a clear, detailed and easily understandable background to the paper made visible by somewhat frenetic media reports. – Ian Musgrave![]()

Ruth Hubbard, Associate Professor, Centre for Research in Geriatric Medicine, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.